The WikipediaMatrix Challenge

How to automatically extract tabular data out of Wikipedia pages? Tables are omnipresent in Wikipedia and incredibly useful for classifying and comparing many “things” (products, food, software, countries, etc.). Yet this huge source of information is hard to exploit by visualization, statistical, spreadsheet, or machine learning tools (think: Tableau, Excel, pandas, R, d3.js, etc.) — the basic reason is that tabular data are not represented in an exploitable tabular format (like the simple CSV format). At first glance, the problem looks quite simple: there should be a piece of code or a library capable of processing some HTML, iterating over some td and tr tags, and producing a good result. In practice, at least to the best of my knowledge, there is not yet reusable and robust solution: corner cases are the norm. In the remainder, I’ll explain why and to what extent the problem is difficult, especially from a testing point of view.

The first experience I had with the problem went back to 2012, when other colleagues and I wanted to mine “product descriptions” or “comparison matrices” out of Wikipedia. We did it on a small sample of pages, and it was OK. In 2015, we expand a bit the scope by targeting the whole data of Wikipedia (using dumps); more than 1 million tabular data, and thousands of corner cases! Our idea, with Guillaume Bécan, was to “formalize” tabular data into a suitable format (richer than CSV) and build a set of tools on top (including a better editor synchronized to Wikipedia). The development of opencompare.org was the incarnation of this idea: the objective seems still relevant and worthy (ping me if you’re interested)! Though our research effort mainly focused on the synthesis and definition of a suitable format for tabular data, a core step remains the extraction of raw tabular data (like in Wikipedia) — I think I under-estimated the difficulty of this task (or didn’t take the time to focus on the problem).

WikipediaMatrix Challenge in the Class

So, last autumn, I decided to revisit our past effort1. Specifically, I challenged students to develop a Java solution to automatically transform tabular data of Wikipedia pages into CSV files. The “WikpediaMatrix problem” (let’s call it) can be addressed in two different ways: given a Wikipedia URL, your extractor can exploit either the HTML (used by the Web browser to depict the page), or the Wikitext (a markup language used in Wikipedia to edit the content of articles). In fact, I asked to implement two extractors and possibly compare them at the end of the project. For a given Wikipedia URL, the goal is to produce as many CSV files as there are tables in the page.

The WikpediaMatrix problem occupied students (8 groups of 4 or 5 students) during 3 months for around 30 hours of lab sessions. The goal was to practice software engineering with a concrete case, including traditional activities: elaboration and writing of a requirements document based on discussions with a client (me!); writing and testing of programs; oral presentations of their solution. The project, part of a software development course, encourages students to use mainstream tools like Maven, JUnit, git, github, Slack, Trello, etc., to choose and rely on external libraries (e.g., Jsoup, Mockito), and to practice what they’ve learned in other courses (e.g., about modeling or software architectures).

I insisted a lot on the importance of testing their own solutions, i.e., with automatic JUnit tests and assertions.

Oracle Problem and Input Diversity

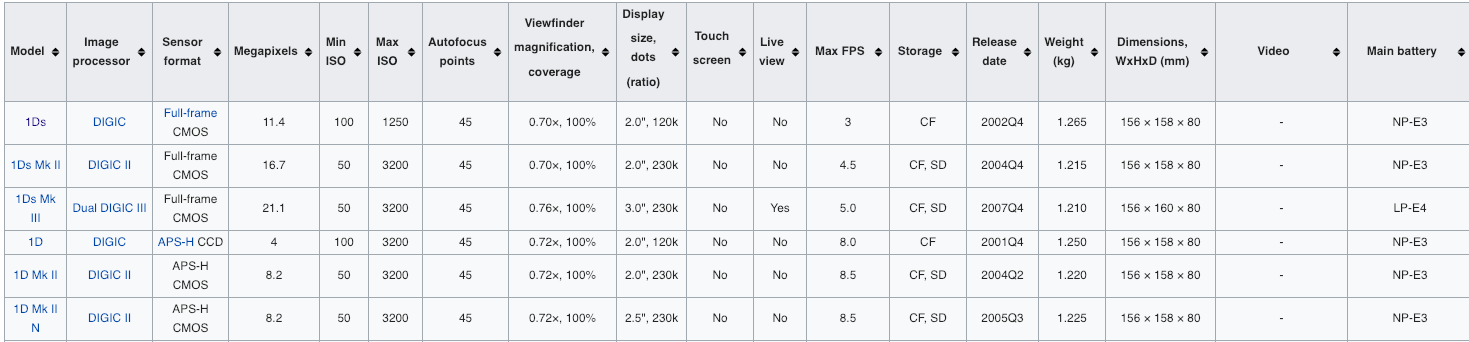

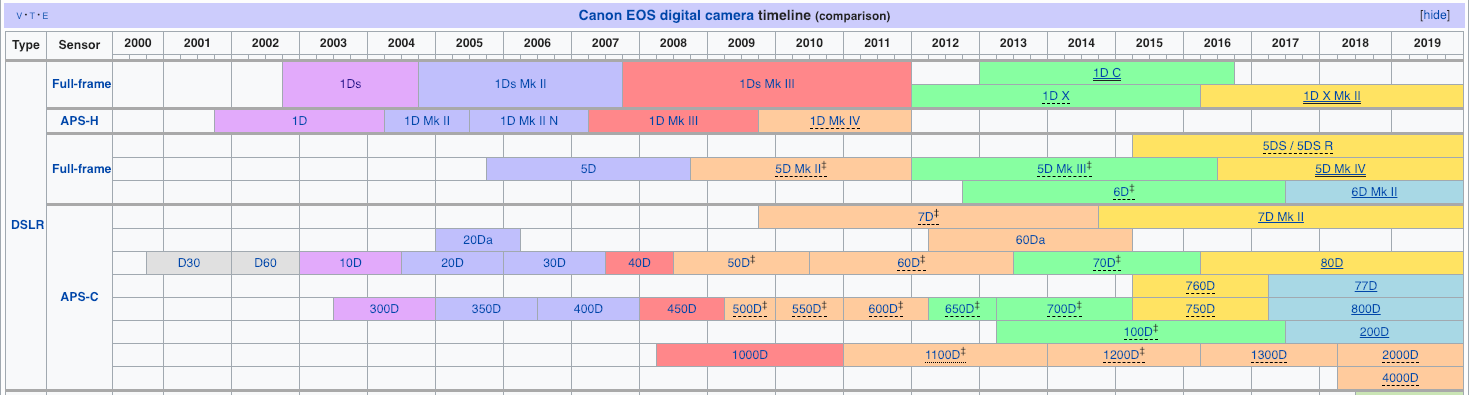

There are different ways of testing such extractors. A basic strategy is to process a given URL, launch the extractors, and assert that the resulting CSV files are equal to a ground truth. For instance, we can consider this URL and write the expected CSV file. This table has 18 columns and 63 rows.

Given the time and effort needed to write the ground truth, you can do it for only a few pages. Another strategy is find more generic ways to test your extractors. A simple one is to verify that your output CSVs are all valid and can be parsed — here you don’t need to specify the specifics of each case. Hence you can apply such generic tests to any Wikipedia URL. The counterpart is that your assertion is very weak and incomplete: the fact your CSV file is valid does not guarantee that its content is correct. In between a generic test and a specific test case with the entire ground-truth, you can find some compromises like just checking that the number of rows is what expected. Overall, we are facing the test oracle problem (see, e.g., these two excellent sruveys s1 or s2): the mechanism in charge of comparing the output to the expected test outcome is hard to instrument, since it has a cost, may be unsound or incomplete.

Another difficulty of testing is related to the diversity of the input. You may think that all Wikipedia tables are structured in the same way, and so the HTML or the Wikitext. It’s clearly not the case. Wikipedia contributors use different mechanisms to create or edit tables. The consequence is that the extractor needs to deal with different cases, and some are surprising (you may well have a table inside a cell). There are also HTML tables that are not real tabular data — tables are just a convenient way to depict the information. For instance, infoboxes are represented as such. Moreover some tabular data may contains disturbing characters (like “,” which is actually a CSV separator) or information that is hard to encode in a CSV (e.g., an image). In addition, Wikitext’s syntax has its own secrets (see, e.g., this report). Last not but least, some tables are very complex with nested columns, merged rows or columns, etc. Pragmatically, it seems reasonable to ignore some tables that are either irrelevant or too complex to encode into the CSV format. For implementing this idea, you need to equip your extractor with a pre-step capable of recognizing when to not extract some data — no need to say you need to test it!

If we recap, the WikipediaMatrix is challenging due to:

- the test oracle problem

- the input data diversity/complexity

When the Instructor is Unable to Test Students…

When originally challenging students, I was of course aware of these two problems, but I did not expect that the problem could backfire and be turned against me (as a teacher in charge of assessing students’ work). Let me explain.

This year, all groups of students had the same subject — so the same requirements and the same objective! I deliberately chose to do so, with the hope of collecting and comparing different results of the WikipediaMatrix problem. In a sense, the 8 groups of students did N-version programming (N=8). My original plan was to write an automated procedure to objectively assess their results (a kind of score than could be used as part of the final mark). I gave a benchmark: a set of 300+ Wikipedia URLs for which I know interesting tabular data exist (basically all Wikipedia articles whose title starts with “Comparison of…”, see the list here. Then participants have to execute their two extractors. For each URL, they have to produce as many CSV files as there are tables, with a naming convention for their files. A simple git clone on their repos and mvn test should allow me to generate all CSV files and then evaluate the result. So what did I do at the end ? I wrote a… testing procedure. And so the test oracle problem previously described naturally applies to me — hence the trap. How to be sure that CSV files of students are (not) correct without having myself a ground truth? If, as an instructor, I cannot objectively assess students’ work, well, it’s not really a confortable situation. (I voluntarily exaggerated a bit the situation since the evaluation also comprises many other aspects, like the quality of the requirements documentation, oral presentation, architecture, testing code, etc.)

Anyway, it sounds an excellent opportunity to tackle the WikipediaMatrix testing problem. In the following, I will briefly expose some experiments and ideas — I am not pretending the problem is resolved ;)

Basic oracles for discriminating the good from the bad

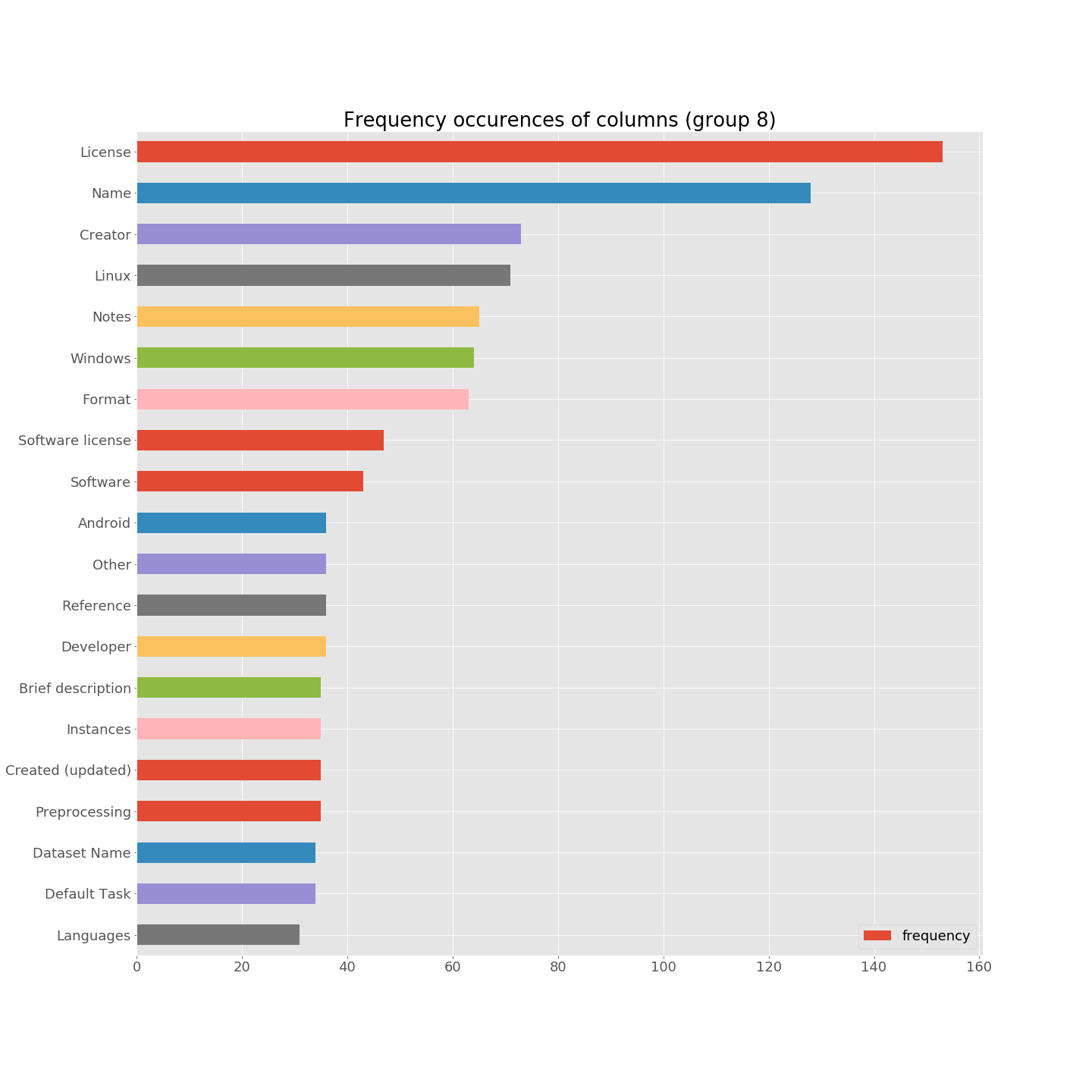

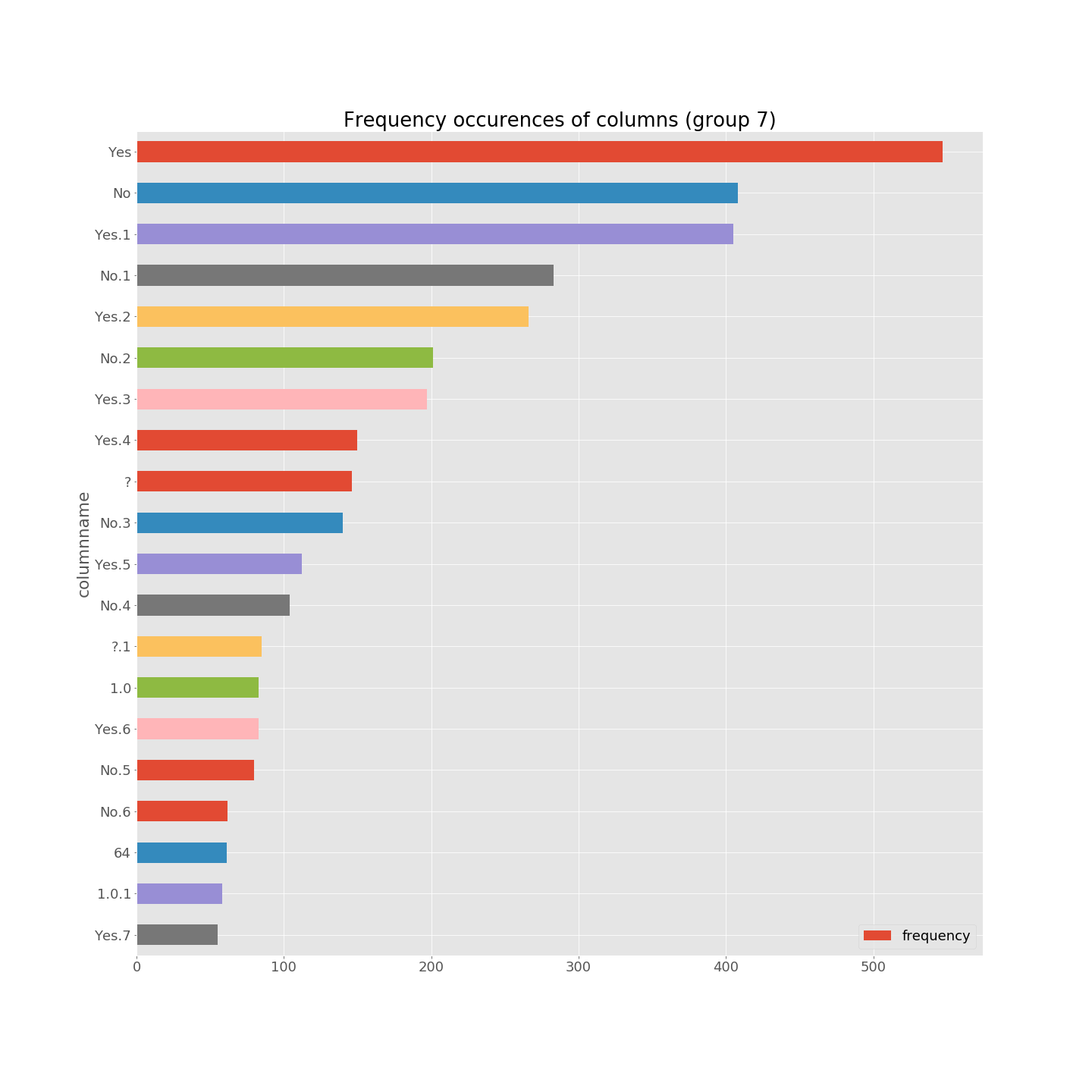

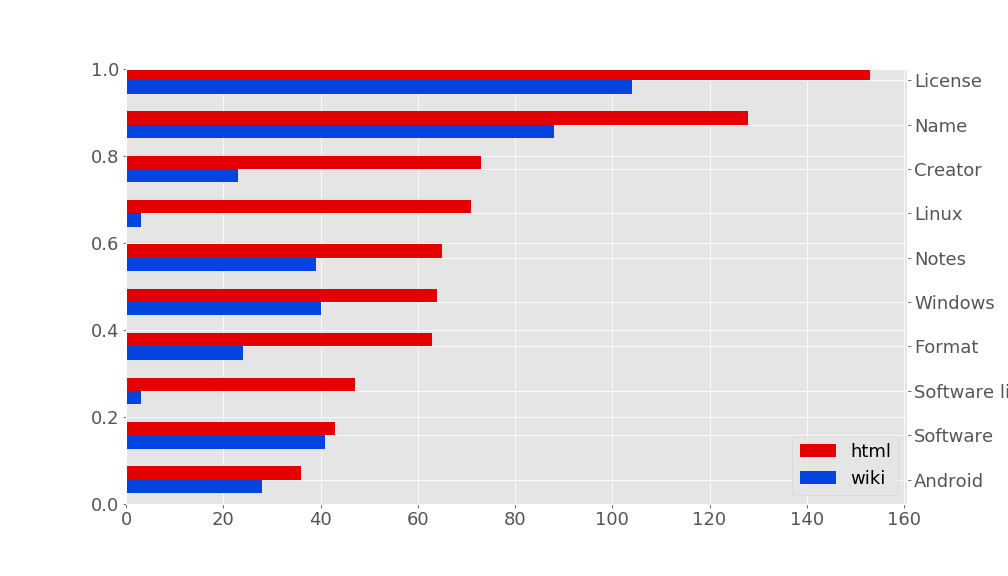

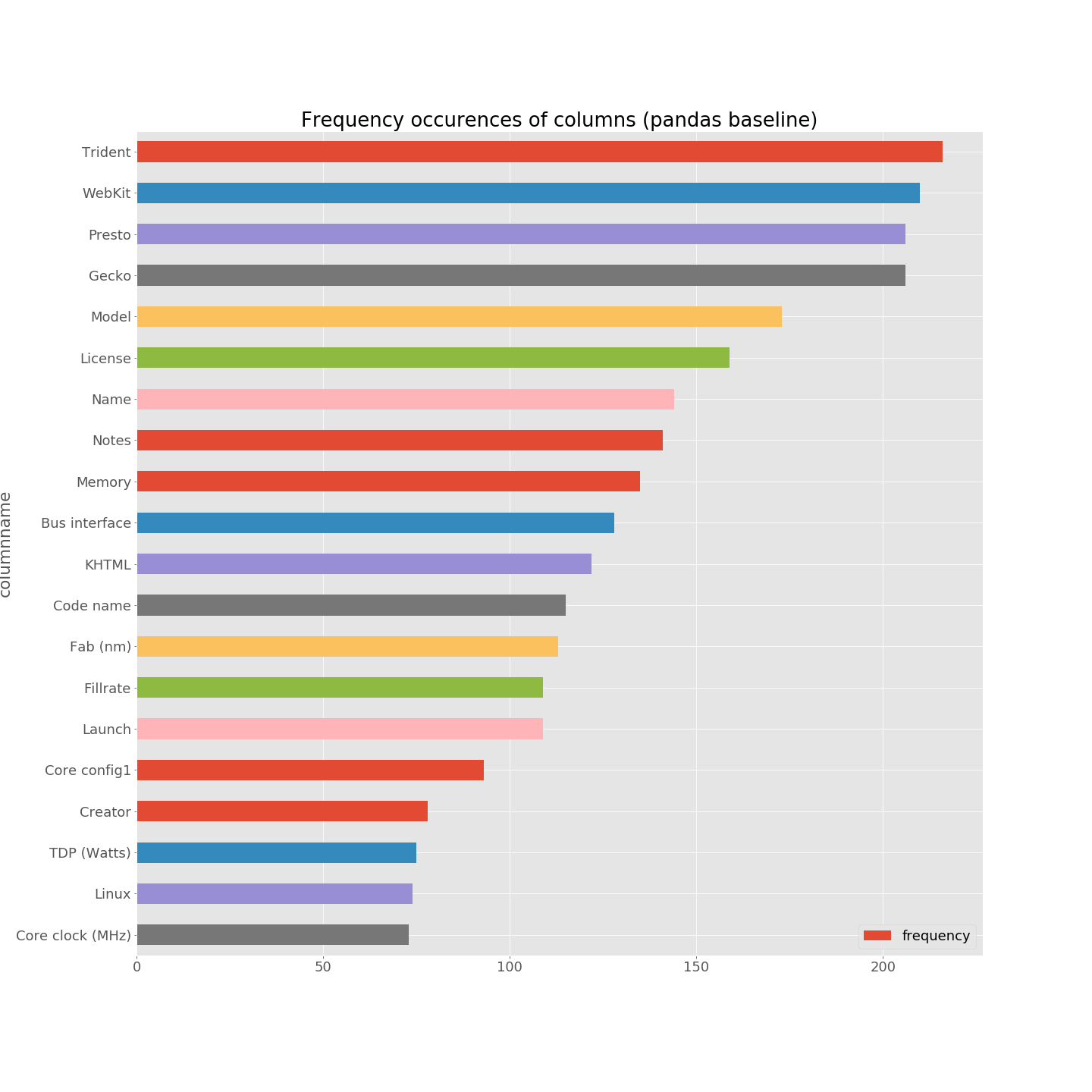

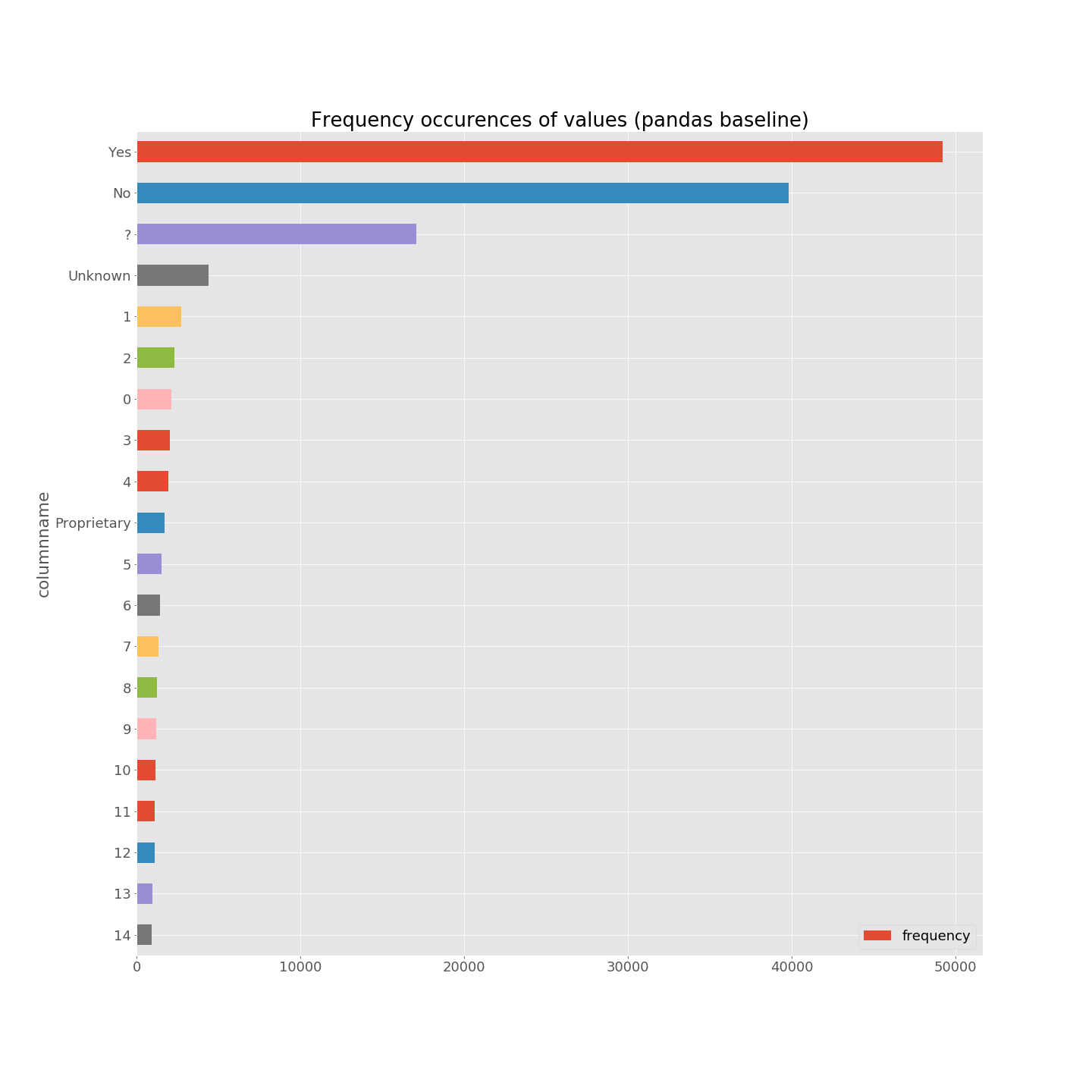

The first thing I did was to implement and combine basic oracles like checking the validity of CSV files (whether they parse or not), eliminating tables for which the number of rows or columns is less than 2, etc. I relied on Python and pandas. Moreover, I have implemented a basic procedure for processing some statistics about the resulting CSV files, more specifically about the column names and cell values. The idea is to collect occurrences’ frequencies of column names (says) on the whole CSV files. Two examples are given below. The first plot sounds reasonable: “License”, “Name”, “Creator”, “Linux”, “Notes”, “Windows” are at the top, and knowledge about Wikipedia matrices confirm such names are indeed frequently used to characterize entries. In the second barplot, we can notice that “Yes” and “No” are the top names of columns. It’s not a good signal: “Yes” and “No” are not column, but rather cell values. It seems that the extractor has failed to correctly locate the table headers.

A quick review of a sample of CSV files confirms the root of the problem (bug).

Such simple checks are quite efficient — it allows me to discriminate good solutions from bad solutions — but you cannot conclude in a fine-grained way. For instance, how to know what is the best solution among the eight implementations?

Comparing implementations

Another idea is to compare extractors. Specifically, there are two ways of comparing implementations:

- you compare the HTML-based extractor with the Wikitext extractor (within a student group solution)

- you compare extractors among students groups (for instance, you compare N=8 HTML-based extractors)

Overall, you can even compare the N=8 * 2=16 extractors.

HTML vs Wikitext extractor

For instance, the barplot below shows a solution that differs between HTML and Wikitext, if we look at how frequently column names appear (I selected top frequent column names of one implementation):

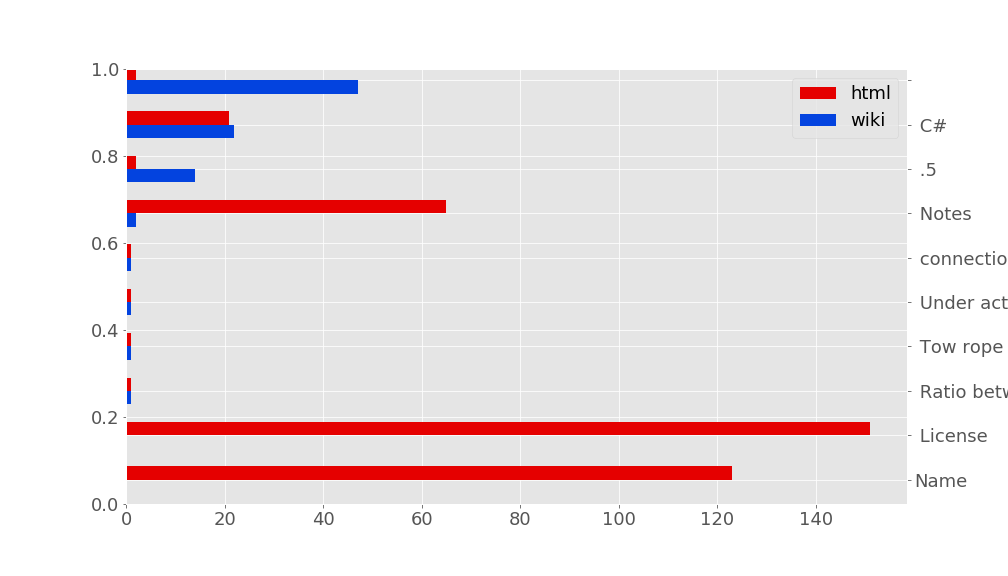

Comparatively, the two solutions are not that different. However, there are more problematic differences (some column names simply do not appear in the dataset of an extractor):

It can help determining the weaknesses of some extractors. We can compare frequencies of cell values as well (instead of only column names).

Note that an exact comparison between the two CSV files (one obtained with the HTML extractor, the other with the Wikitext extractor) may be unfair or too strict. In particular, the data sources differ a bit. For instance, if you look at the raw content of Wikitext, many cell values are {{{Yes}}} and not “Yes” as simply depicted in the HTML.

N-variants testing

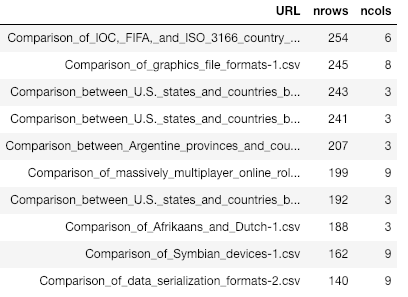

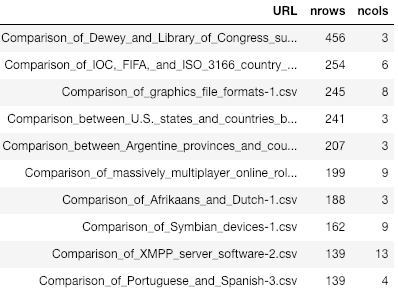

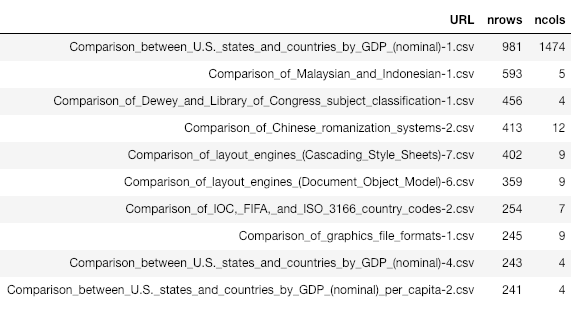

We can reuse similar treatments among competing extractors. We can also apply lightweight techniques like comparing the number of rows and columns per tables and URLs. Below is a comparison between the ten larger tables (with regards to the number of rows) as obtained by two solutions:

The results for “IOC, FIFA and ISO”, “Afrikaans and Dutch”, “massively multiplayers”, etc. are exactly the same, but the “Dewey and Library…” case differs.

We could also compare the entire content, file by file (again, a strict equality may be too strict). Anyway, whatever the “oracle” used, an open question remains: who is right when things differ? Solution A-with-HTML or solution B-with-Wikitext?

A pandas to the rescue?

I decided to implement my own extractor (out of HTML only) — my goal was to build a strong baseline that will rule them all. I relied not on Java but on Python, and I used the pandas facility to extract CSV files out of HTML. A few lines of code, and then we are done, right?

html = urllib.request.urlopen(url).read().decode("utf-8") # get_wikipedia_html

dfs = pd.read_html(html, header=0) # there may be more than one table

ntable = 1

# serialize into CSV files

for df in dfs:

df.to_csv(sanitize_filename(url) + "-" + str(ntable) + ".csv")

ntable = ntable + 1

The real code is more complex, but the idea is here: reuse a popular, external library and we can then compare it with other implementations. One of the good feature of pandas is that the support for serializing dataframes into CSV is quite robust. What are the results of the pandas-based implementation? Does it superseed previous implementations?

Well, we can only give insights. Looking at column names and cell values, it is quite consistent with other implementations. Yet we can notice some strange facts: “Trident”, “WebKit”, “Presto”, and “Gecko” seem over-represented (after manual investigation, a Wikipedia page causes troubles and leads to such outliers). Also, numbers are vastly present in cell values (it’s not necessarily the case for other implementation).

The top 10 of large tables gives also interesting insights. Clearly, the first table is due to a bug in my pandas-based implementation (you can confirm it with a manual inspection) while we also found similar results to the other top 10 depicted above.

We cannot claim that the pandas-based implementation is the best; we rather have more problems now ;)

Human Oracle

Again: who is right among solutions of the WikipediaMatrix problem? Though the comparison of different implementations gives interesting insights, sometimes we need to rely on some expertise or manual reviews — yes, we need humans.

I’ve developed a simple prototype that can help in this task. The idea is to build the means to visually confront the original table with the extracted table. Technically, for each Wikipedia URL, a program produces a Web page with:

- a screenshot of the original Wikipedia (thanks to selenium and webdriver)

- an HTML representation of the CSV file (pandas has a nice support to expert dataframes to HTML)

Then the reviewing workflow can be this one:

- based on observations/statistics of an extractor, identify suspicious cases and have a look at the possible problem. An example is a column name that seems too frequently present or a table with a large number of rows.

- based on differences between extractors, investigate suspicious cases with the prototype and determine what implementation is right (if any).

It was useful, but obviously the effort is important and cannot scale to thousands of tabular data.

Conclusion

The WikipediaMatrix challenge consists in programming a procedure capable of extracting tabular data out of any Wikipedia page, either through the exploitation of HTML or Wikitext. It is a difficult task, mainly because of the diversity of Wikipedia pages and the difficulty of assessing your own procedure. You can succeed on very simple cases, but fail on others — you realize it when it’s too late ;(

From a teaching perspective, it’s an interesting support to challenge students. I’m replicating the effort with other students, with a different background. From a software engineering perspective, it’s a nice illustration of the problems we can face when testing — the infamous oracle problem. From a Wikipedia perspective, we definitely need tools capable of easing the exploitation of the incredible amount of data — here tabular data. Maybe this experience can also motivate some discussions on the way tabular data are represented and edited by contributors.

From a research perspective, there are many directions to explore. Just to name a few:

- there are so many Wikipedia articles (millions) and clearly we cannot test all of them. It would be nice to identify a subset of representative and problematic cases in such a way we can reduce both the computational cost and the human effort

- devising an established benchmark with metrics: it can be used to automatically assess the quality of an extractor. Right now, different measures are made, but we miss an integrated and actionable score.

- does an HTML-based extractor for Wikipedia generalize to any Web pages?

I’ve put the source code of my procedures (Jupyter notebooks, see e.g., benchanalysis) as well as data (e.g., CSV files) on a Github repository My hope is that we can collectively improve the quality of extractors (why not launching a competition?) and also better understand the means to achieve that goal. Don’t hesitate to ping me if you want to be involved with the WikipediaMatrix challenge!

-

As usual, I am trying to find a good excuse to combine teaching with research interests (here: about software development, testing, and reverse engineering/mining data). In previous years, the “projects” were quitte different and were about mining openfoodfacts, wikidata, wikipedia, but also modernizing open source projects, analysing chess data or 3D printing programs. ↩

software engineering software testing data